State of disunion: The impact of US funding cuts on global health R&D

By Impact Global Health 10 November 2025

What this report tells us

Up until 2025, the US has played an incredibly significant role in global health R&D, particularly in basic research, EIDs and maternal health

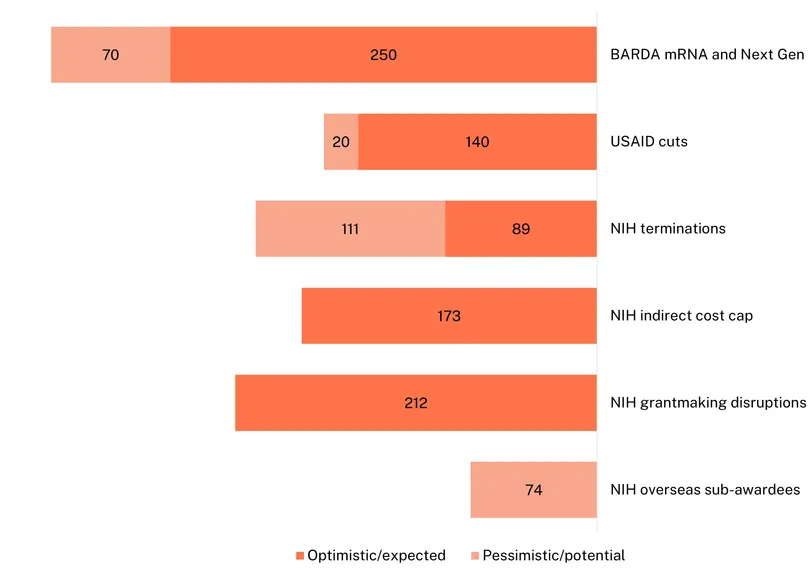

The cuts that have already been made to specific grants, and to the disruption of the NIH’s ability to approve new funding, will have a substantial impact on 2025 funding, reducing it by a projected $474m, or 14%

The dismantling of USAID is projected to reduce the 2025 global health R&D funding it used to oversee by at least $140m (83%) and likely closer to $160m, with particularly heavy reductions in its funding to CEPI and its support for contraception and multipurpose prevention technologies

Terminated NIH grants will reduce funding for HIV R&D by around $18m, COVID by $15m and malaria by $14m, while the largest proportional cuts will fall on Mpox (9% reduction in NIH funding), maternal iron deficiency (9%), uterine fibroids (8%) and flaviviruses like Zika (8%)

A proposed 15% cap on indirect costs would reduce 2025 funding by a further $173m, while a ban on foreign subawardees – if recipients cannot restructure to avoid its effects – could impact subawards worth a potential $74m

Preventing the NIH from issuing new grants, as appeared to be the case throughout much of 2025, would have an even larger impact, likely at least $212m, unless grant reviewers can make up for lost time

The termination of BARDA’s funding for MRNA and Project NextGen R&D will reduce its 2025 funding for global health by at least $250m and potentially more than $320m

The President’s proposed departmental budget cuts, if applied at similar rates to global health, would reduce US public R&D funding by almost 40%, or $1.8bn

Without US funding, many areas of global health R&D would grind to a halt. The areas that are particularly vulnerable to long-term reductions in US funding are early-stage (especially basic) research, biologics and maternal health, with several areas exclusively reliant on US funding over the last decade

Areas which have maintained a balance between US, private sector and philanthropic funding provide a potential road map for the areas most exposed to funding cuts

Funders outside the US government need to understand what is likely to be lost, identify the specific gaps in funding opened up by the loss of US support and decide, ideally collectively, which most urgently need to be filled

A fall in global health R&D funding to levels last seen a decade ago is not a cause for despair, but it does mean that the already very high return on investment from funding R&D has become higher still: when funding is scarce, every dollar matters more.

Background

Cuts to US ODA and R&D funding

Since January 2025, the US government has begun reassessing its role in health and science at home and abroad. Early policy moves, alongside a broader review of foreign assistance and biomedical research, have created real uncertainty for the parts of the R&D ecosystem that underpin global health and pandemic preparedness. This matters because, while the sums at issue are small in the context of overall US spending, they account for a meaningful share of the global financing available for neglected diseases, emerging infectious diseases and women's health. Even modest shifts in US priorities can therefore seriously undermine pipelines, partnerships, and delivery timelines.

This report focuses on the research and development dimension of those changes. We document the changes made and proposed to date and estimate their implications for global health R&D. In doing so, we recognise that these developments are just a small part of the wider changes affecting public health and science more generally: to programmes for disease surveillance, to scientific oversight and emergency response, and to the distribution of vaccines and therapeutics, all of which shape the environment in which R&D occurs and underpin its potential to deliver real change. Our intent is not to litigate these choices, but to understand their practical consequences for a field where the US remains a central figure, even in the wake of the proposed cuts.

We examine several policy and funding changes made since the beginning of 2025: the effective dissolution of USAID as an independent entity; terminations or pauses of selected NIH awards; modifications to grant approval processes and indirect-cost limits; potential restrictions on overseas sub-awardees; and the halting of BARDA’s Project NextGen and mRNA-related programmes. In some places, judicial rulings have temporarily reinstated funding; in others, implementation is ongoing. We have used the latest available information to estimate near-term impacts while acknowledging that the landscape is still a moving picture and figures may shift as legal and administrative processes evolve.

We also acknowledge that other reports may show larger cuts than those we outline here. We have arrived at lower estimates partly in because we exclude instances where grants have been reinstated– possibly temporarily – from our headline totals, but mostly because our focus is exclusively on biomedical R&D: while recognising their vital importance, we exclude areas outside this scope—such as social science and implementation research, other disease areas beyond our defined G-FINDER set, and broader reductions in health systems and surveillance spending. As far as possible, we have attempted to exclusively report reductions in funding which would have been included in the 2025 G-FINDER survey, leading to meaningfully different – and typically smaller – estimates than other analyses.

To ground the analysis, we begin with the pre-2025 baseline for US public R&D funding in global health. We then estimate observed and likely near-term effects of the policies as they are most likely to be implemented, before turning to scenarios for longer-term budget setting that are less susceptible to litigation. The final section highlights the areas which are particularly reliant on US funding, as well as features that appear to confer resilience, before laying out some practical steps funders can take in response to the changes in US funding.

US public funding for global health R&D

Historically, the US has played a significant role in funding global health R&D

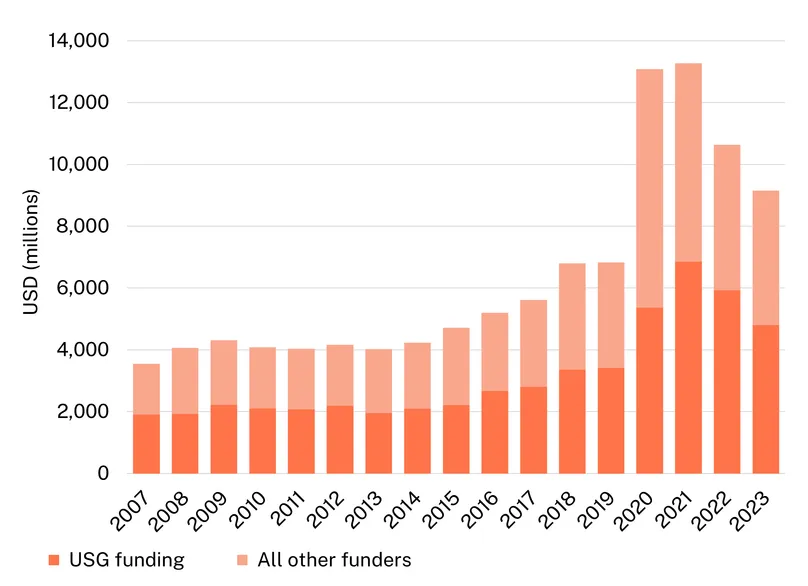

Funding from the US government has accounted for half of all funding for global health R&D since 2007, with the NIH alone accounting for 38% of the global total. The US has consistently provided at least 47% of global R&D funding almost every year but one since the G-FINDER survey began in 2007.

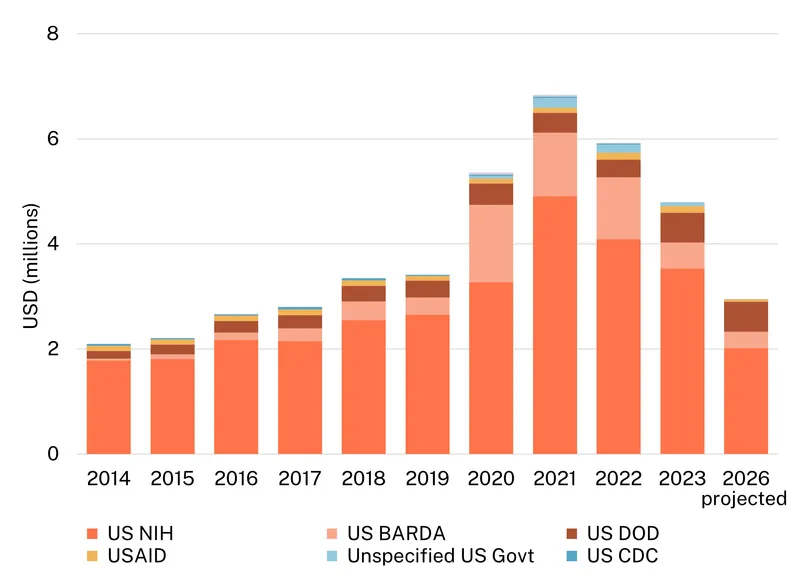

Figure 1. US government in comparison to all other global funders, 2007-2023

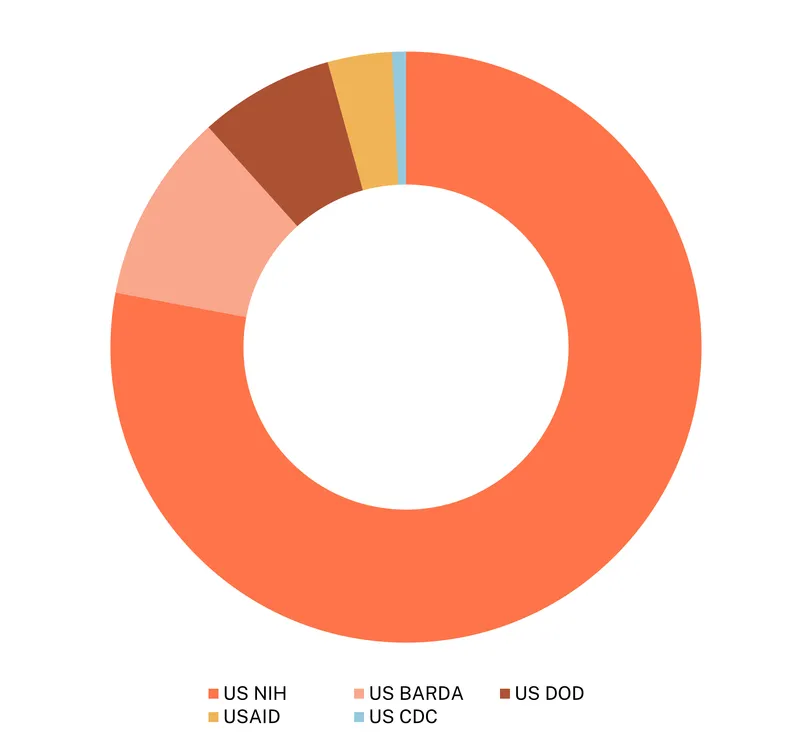

Since 2007, the US government has invested a total of $54 billion in global health R&D[1], essentially all of it from five agencies – the NIH, BARDA, DOD, USAID and CDC. Within these five, the NIH was responsible for more than three-quarters of the total ($41bn, 77%), with much smaller shares from USAID (around 3% of 2023 US government funding) and especially the CDC (0.1%). Figure 2, below, shows the dominant role traditionally played by the NIH.

Figure 2. US government global health R&D funding by agency (2007-2023)

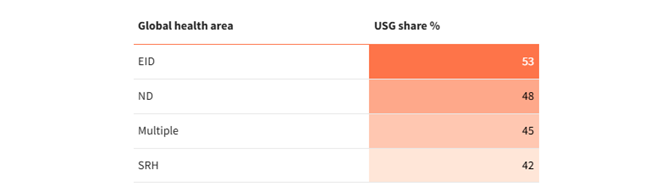

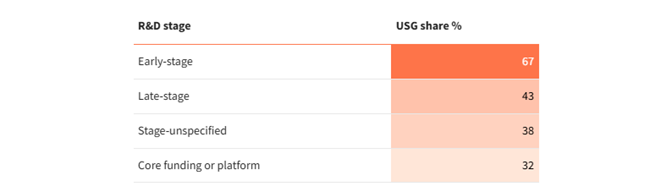

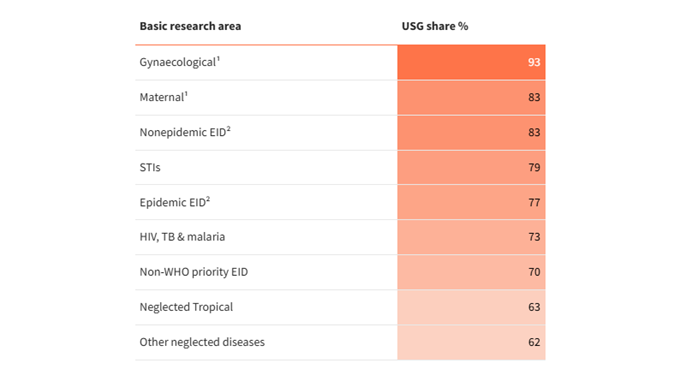

US public funding plays an especially vital role in some key domains, including early-stage research, EIDs and women’s health

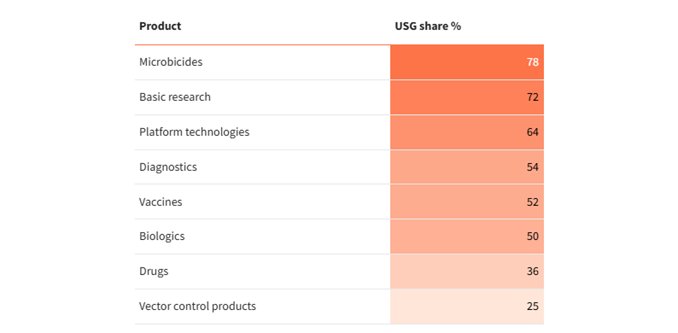

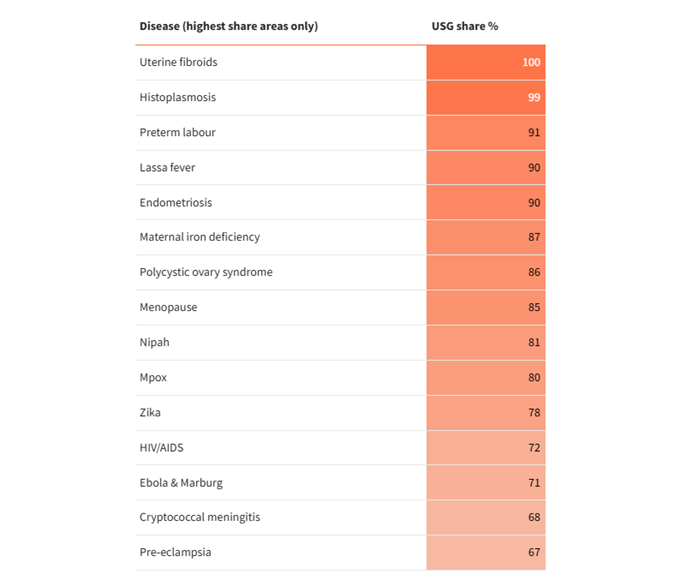

While the US government provides half of all global health R&D funding, its contributions are unevenly distributed across different areas. The NIH’s focus on basic and early-stage research means that US public funding tilts towards that area, with less of a focus on late-stage research, particularly for some products or diseases. The NIH is also often nearly the only source of funding for the most commercially neglected areas of global health, notably gynaecological (89%) and maternal health R&D (64%), as well as under-the-radar EIDs. In contrast, areas like neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), STIs, and contraception have more diversified funders bases, mostly thanks to greater engagement from philanthropic and private actors. The tables below show which areas are proportionally most exposed to a reduction in US funding based on the funding they received over the last decade.

Share of funding received from the US government, 2014-2023

By stage, health area, product, & disease

[1] In this report ‘global health R&D’ means funding for biopharmaceutical research and development targeting neglected and emerging infectious diseases and women’s health. See our survey scope and methodology for specific details of the diseases, products and conditions included.

Analysis

Cuts to 2025 funding have already had a significant impact on global health R&D

This section projects the impact of actual or proposed policy changes on 2025 US public funding for global health R&D. These predictions are subject to the evolving details of the proposed changes and the litigation and potential future congressional review of the existing ones, but, where possible, we have tried to give a sense of the range of possible impacts.

The dissolution of USAID will impact the search for EID vaccines and HIV prevention

On January 20, 2025, the Trump administration released Executive Order 14169, Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid.

Its key provisions included a 90-day pause on all new foreign development assistance obligations and disbursements, including to NGOs, international organisations, and contractors, unless exempted by the Secretary of State. Exemptions were later provided only for narrowly defined emergency humanitarian programs, but explicitly excluding funding for activities related to family planning, DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) programs, or transgender medical services.

On February 13, 2025, the U.S. District Court for D.C. issued a temporary restraining order requiring the administration to restore foreign aid funding that had been legally appropriated and to suspend enforcement of the freeze on existing awards.

On March 10, 2025, the Secretary of State announced that approximately 5,200 of USAID’s 6,200 programs – about 83% – had been cancelled. The remaining 1,000 programs were to be integrated into the State Department’s portfolio. As of July 1, 2025, USAID has officially ceased operations, with an estimated 97% of its staff laid off and much of its undisbursed funding rescinded by the Senate.

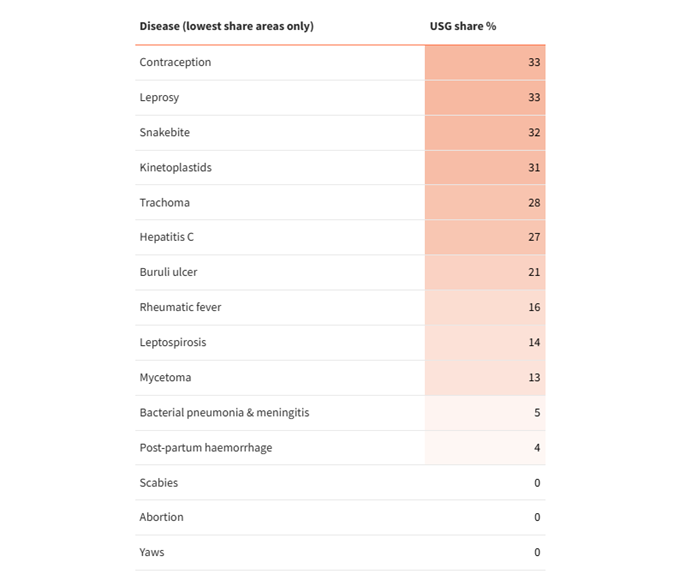

The dissolution of USAID as an agency means that even confirming the most recent year of historical funding is challenging. In the absence of direct USAID reporting of its 2024 funding, we have estimated the impact of its dissolution based on the assumption that its 2023 R&D funding will be reduced on a pro rata basis by the estimated 83% reduction in its overall budget, with a manual adjustment to reflect the $100m in 2024 USAID funding reported by CEPI, as set out in Figure 3, below. This assumption is likely to be optimistic, since little of USAID’s R&D activity is likely to fall within the emergency humanitarian exemption, and a substantial portion relates to reproductive health activities, which appear to have been completely defunded.

Figure 3. Actual and projected USAID R&D funding in millions of USD, 2015-2024

In raw dollar terms, the impact of USAID’s dissolution on global health R&D will fall most heavily on the pandemic preparedness, with USAID’s recent contributions to CEPI – supporting R&D across multiple EIDs – totalling more than $150m over the previous two years. The scale of the funding cut for neglected disease R&D is comparatively smaller, largely since USAID’s funding for this area had been in long-term decline; unlike the EID investment, however, which was a relatively recent phenomenon, the shuttering of USAID has ended longstanding support for key neglected disease R&D programmes, particularly for HIV. In addition, USAID had played an important role in funding for contraception and multipurpose prevention technologies (‘MPTs’, which prevent STIs as well as providing contraception), with USAID accounting for 13% of global MPT R&D funding and 5% of contraceptive R&D and serving as the largest single public funder of long-acting reversible contraceptive R&D.

The overall 2025 impact of shutting down USAID is likely to be somewhere between $140m, if our optimistic scenario where cuts to overall spending fall pro rata on R&D is approximately true, and $160m, if payments to CEPI and contraception-related funding are removed entirely.

Grant-making delays at the NIH have the biggest potential impact

Review, termination and partial reinstatement of ongoing NIH grants

Beginning in February 2025, NIH initiated widespread terminations of research grants deemed inconsistent with agency priorities targeting topics such as DEI, gender identity, COVID-19, and health disparities. Between February and early May, an estimated 777 grants were cut, accounting for over $1.9 billion, including more than $1 billion directed to medical schools and hospitals.

By late May, around 2,100 NIH grants, totalling an estimated $9.5 billion, had been terminated, nearly 30% of which had supported clinical studies.

In mid-June a federal judge ordered the reinstatement of hundreds of terminated grants, causing the NIH to issue a halt to further terminations.

Delayed appropriations

Alongside the terminations, NIH greatly reduced its issuing of new grants relative to previous years. The cause of these delays included the review and termination process outlined above, a hold on issuing grants with foreign subawardees, and the inability of the NIH’s scientific advisory committees and peer review study sections to meet following a change to notice requirements. As of August 2025, the NIH had resumed awarding new grants, though still at a reduced pace, with priority given to clinical trials and projects deemed essential for public health.

The combined effect of these delays is that the NIH as a whole has failed to allocate significantly more than $5bn in appropriated funds which are required to be obligated to grantees prior to the end of the US government fiscal year on 30 September.

Cap on indirect costs

In February 2025, NIH announced a uniform cap of 15% on indirect cost rate (also known as overhead, or ‘Facilities & Administrative’ costs) for both new and existing NIH grants. The proposed cap would replace the previous system of negotiating rates on a case-by-case basis, which often resulted in indirect cost rates of between 25% and 50%.

As with the other changes outlined above, litigation challenging the revised policy is ongoing, with an injunction currently in place preventing its implementation.

Background

Since the inception of the G-FINDER survey in 2007, the US NIH had provided 38.5% of global health R&D funding, including 38.7% of funding in 2023. It has been by far the largest single funder, accounting for a larger share of overall R&D than the next eleven largest funders put together. Changes to funding from the NIH have the potential to completely transform the state of global health R&D.

In this section, we attempt to estimate the impact of the most significant known changes to NIH funding.

Effect of ongoing grant termination

Cross referencing the value of terminated grants listed by Grant Witness (formerly Grant Watch) as of 25 August 2025 against NIH global health R&D funding programmes active in 2024 suggests that a total of $89m in 2025 funding has been terminated and not reinstated. A further $112m in estimated 2025 funding was terminated and then subsequently (as of August 2025) reinstated, presumably causing significant disruption to these projects even if all funds are ultimately disbursed.

The $89m in (currently) terminated grants would represent 2.8% of the NIH’s 2024 funding, with the reinstated grants accounting for a further 3.5%. This will have placed substantial downward pressure on its overall funding in 2025 but is well within the usual year-to-year variation we typically see in NIH disbursements.

The largest cuts in absolute terms were to HIV R&D (19% of the total, around $17m), COVID (15%, $13m) and malaria (12%, $11m) while the largest proportional cuts were for Mpox (an estimated 9% reduction), maternal iron deficiency (9%), uterine fibroids (8%) and flaviviruses like Zika (7%). The roughly $11m reduction in malaria funding was both large in absolute terms and represented a fairly substantial (5%) share of its 2024 NIH funding.

Effect of capping indirect costs

The proposed 15% cap on indirect costs (‘overheads’), though currently subject to an injunction, would have a significant impact on the funding we include in our measure of global health R&D. While overhead funding does not flow directly to the R&D projects it is associated with, it does play a key role in supporting the wider research infrastructure on which global health R&D relies. Since global health projects are likely to be partly cross subsidised by overhead funding associated with other kinds of R&D, our projection of the direct effect of an overhead cap on global health funding is likely to underestimate its true impact on the resources available in the future.

An analysis of overhead rates for global health R&D grants shows an average overhead ratio of 26%. If overhead were capped at 15% for each individual grant, the estimated effect would be to reduce NIH payments to academic and other research institutions by 7.4%, or around $173m based on projected (pre-cuts) 2025 NIH funding. Rather than falling on the specific projects with high overheads, these cuts would impact the overall R&D infrastructure of recipient institutions, likely falling most heavily – in absolute terms – on the COVID, HIV and TB R&D these organisations specialise in.

Effect of disruptions in issuing new grants

An analysis of NIH grant-making suggests that, on average, approximately 36% of its global health R&D spending each year comes from (new) grants issued that year. As a result, the value of NIH funding is incredibly vulnerable to the kinds of disruptions in issuing new grants outlined above.

We lack any way of measuring the specific grants not issued as a result of delays to assessment and approval. Analysis by the American Association of Medical Colleges suggests that there has been an 18% reduction in overall new grants (including competitive renewals) across the entire NIH portfolio, and we might reasonably worry that global health might have been disproportionately impacted due to its exposure to terminations and restrictions on foreign subawardees (see below).

Taking the 18% figure as a (potentially optimistic) baseline would suggest a similarly sized reduction in the 36% of NIH funding which would typically be made up of new grants in 2025, implying a fall in overall NIH funding of around 6.5%, or roughly $212m, relative to a pre-cuts baseline.

If the award of global health grants had been entirely disrupted – an unrealistic worst-case scenario – then the impact would be far larger: a reduction of more than $1bn in 2025 NIH funding against the projected baseline of $3.3bn.

Potential effect of restrictions on overseas subawardees

The effects of the temporary stay and the proposed permanent ban on providing NIH funding to foreign (non-US) sub-awardees are even more difficult to estimate than the other changes in policy considered above. Since the terms of the proposed restrictions remain uncertain, it may be the case that grants which would have been approved under the old rules can be restructured as separate direct grants to foreign and domestic recipients. In this case, the impact of the policy might be limited to a transitional period of disrupted funding and a slight increase in administrative burden.

Further complicating matters, our data on global health R&D funding does not distinguish between primary recipients and subawards, making it difficult to determine what portion of an overseas subaward is relevant to global health.

Given these complications, we can only say that the effect of a permanent ban on foreign subawards would range from somewhere close to zero, if awardees can adapt seamlessly, to as much as $74m annually, if restructuring grants is difficult and a large proportion of overseas spending in partly global health-related grants is relevant to global health. The upper end of this range would represent a roughly 2.5% reduction in NIH spending, but in practice, the impact is likely to be much lower.

Cuts at BARDA focus on next-gen COVID vaccines and mRNA

In April 2025, BARDA appears to have terminated several of the grants under its Project NextGen, which was established in April 2023 with up to $5bn in potential funding to develop vaccines and therapeutics for COVID and other EIDs. Three of the major awards under this project appear to have been terminated: contracts worth up to $388m with Geovax and its research partners for a Phase 2b multi-antigen COVID vaccine; a potential $389m to Codagenix for an intranasal COVID vaccine; and up to $338m to CastleVax for the development of its intranasal COVID vaccine. Two further NextGen contracts, including one for the development of an oral COVID vaccine, were temporarily put on hold but, as of this writing, appear to have been reinstated.

These cuts were followed in August 2025 by the termination of 22 BARDA-backed mRNA R&D projects, including an inhalable powder-based mRNA vaccine under development by Emory University and Tiba Biotech’s RNAi-based therapeutic for H1N1 influenza. The total value of the cuts to mRNA R&D was listed as $500m, likely based on the potential maximum value of the contracts involved.

The limited availability of annualised BARDA funding data makes it difficult to estimate the 2025 impact of these cuts on global health R&D. Based on our standard methodology of pro rating the value of BARDA’s contracts across their working life, so that 25% of the funding from a four year contract is assumed to fall in its first year, we estimate that BARDA’s 2025 funding will be somewhere between $250m and $320m lower than would otherwise be have been the case. The exact value depends on the extent to which a large contract for vaccine trials listed as ‘partially terminated’ has been defunded and may understate the impact of the changes to mRNA funding.

This would be a significant reduction in BARDA’s overall funding relative to the $500m it provided in 2023.

Radical changes at the CDC will have limited impact on R&D

The CDC has historically played only a small role in global health R&D, contributing an average of $29m per year between 2014 and 2022 – or less than 1% of US government funding. In 2023, its R&D funding plummeted by 75% to a then record-low $4.4m, before falling again, to less than $4m, in 2024.

As a result of its small remaining role in global health R&D, changes in policy and large-scale layoffs at the CDC – which include the departure of many senior staff members and the abandonment of several of its long-term disease tracking projects – may have serious consequences for public health but are unlikely to have a substantial impact on R&D spending.

US public funding in 2025 has likely fallen by nearly $900m

Subject to the uncertainties outlined above, our ‘best guess’ central estimate for the immediate impact of funding cuts and other policy changes on global health R&D in 2025 is approximately $880m,[1]. This would imply a roughly 18% reduction in the US government’s contribution to global health R&D equating to a fall of perhaps half that size – around 8% – in global funding.

Figure 4, below compares the relative impact of the different changes, including a wider range of scenarios discussed above, but not included in the $880m central estimate.

Figure 4. Comparing the impact of policy changes

[1] This assumes the pessimistic scenario for USAID – full termination of funding to CEPI and for contraception – no impact from BARDA’s partial termination – no impact on reinstated grants, no impact from restrictions on foreign subawardees and the optimistic scenario for grant-making disruptions – i.e. impact on global health in line with overall impact.

Discussion

How can global health navigate a world with greatly reduced US funding?

In this section of the report, we move from modelling the immediate consequences of the funding cuts currently underway to considering how global health R&D can adapt to a permanent shift in US government priorities.

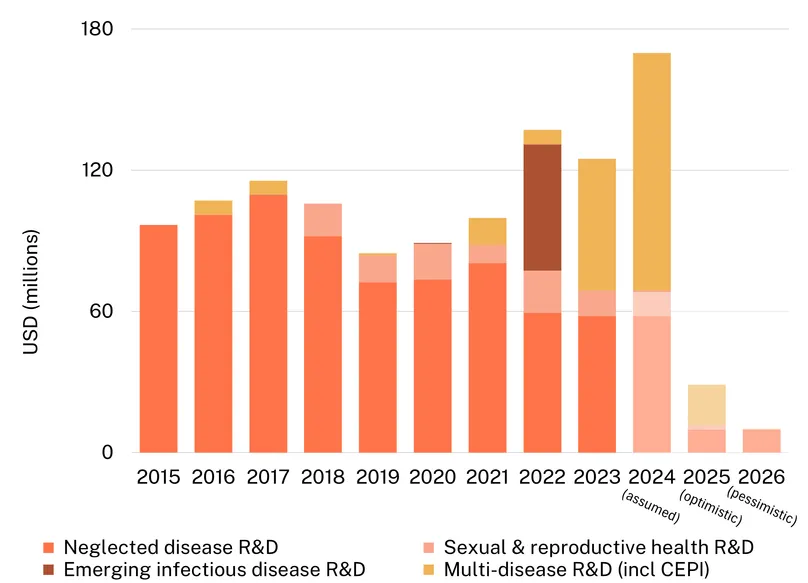

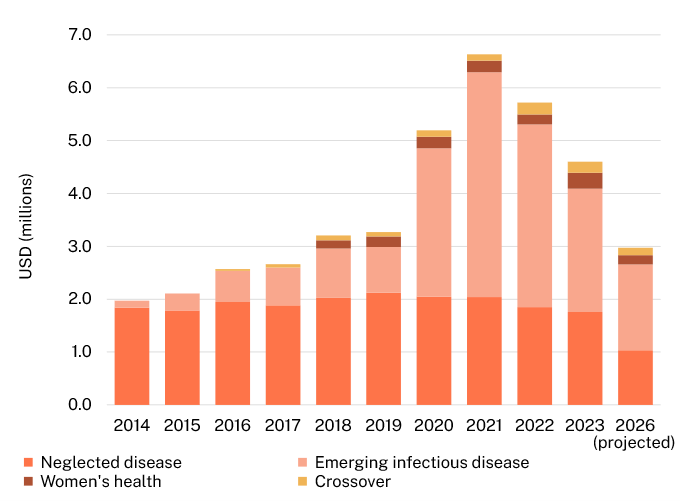

Figure 5. Projected US public funding based on the Presidential Budget Request

The US government has historically been the single most significant funder of global health R&D, providing almost exactly half of all global health R&D funding over the last decade. The cuts to 2025 funding, and especially the proposed cuts shown above, suggest that the era of being able to rely on the US may be coming to an end.

Figure 5, above, estimates how the Department-level budget cuts proposed in the 2025 Presidential Budget Request (PBR) would impact global health R&D if the suggested cuts were applied proportionately to each organisation’s global health activities. In reality, though, the 43% cut in NIH funding contained in the PBR would likely fall even more heavily on global health than on the NIH’s other areas of research, making the chart above an optimistic projection – the real impact would likely be even larger.

The proposed budget would radically reshape US funding priorities and unwind years of progress

These proposed reductions would return US public R&D funding to something like its 2017 level (in real, inflation-adjusted terms), wiping out the growth that had led to a peak in global neglected disease R&D in 2018 and 19, as well as the growth in funding for EIDs and platform technologies we saw in the wake of COVID.[1] It would leave a gap of just over $1.8bn relative to 2023 – nearly double all the 2023 funding provided by the Gates Foundation, the second largest individual funder.

As shown in Figure 5, above, remaining funding would be more skewed towards the priorities of the US DOD, which our projections show rising from 12% of the total in 2023 to 19% in 2026 and beyond. The DOD’s R&D programme spans multiple areas, with vaccines accounting for about one-third (36%) of total R&D spend from 2013–2022, mostly focusing on diseases which might affect deployed servicemembers. In 2023, though, the pattern of DOD funding changed significantly, with a big increase in funding skewed heavily towards EID-focused platform technologies, especially biologic and diagnostic platforms. Its vaccine funding fell sharply, to less than 3% of the new (now much larger) total, alongside a significant increase in vaccine funding from BARDA – much of which has since been terminated.

Proposed cuts would decrease the focus on vaccines and basic research

Assuming the existing product distribution of funders’ budgets is unchanged, the proposed budget would see a 41% decrease in US spending on vaccine development, leading to a 21% reduction in global vaccine R&D. The cancellation of BARDA’s Project Next Gen and MRNA funding discussed above, in combination with this disproportionate impact of the PBR on vaccine funding, mean that post-2025 US funding is likely to be much less focused on vaccines than has historically been the case.

The other area most affected by the existing and proposed funding cuts is likely to be funding for basic research. Assuming unchanged distribution of spending, the PBR would lead to 42% reduction in US public funding for basic research, and consequently a 31% fall in global basic research funding – even larger than the impacts on vaccine R&D outlined above. This reflects the key role played by the NIH, which has funded just over 70% of the world’s basic research addressing global health priorities since 2007. Since basic research has historically constituted a third of NIH’s global health R&D funding, compared to less than 10% of total funding from all other sources, the cuts and disruptions to NIH funding will fall disproportionately on basic research.

As the table below shows, there are a dozen areas of global health for which the US has provided at least 80% of the global basic research funding, and three – including maternal iron deficiency – for which there has been no other reported funding at all.

Basic research areas with the highest US government funding shares, 2014-2023

1 Many gynaecological conditions and a smaller share of maternal health conditions were included in the survey for the first time in 2023, meaning the concentration of reported funding may partly reflect initially limited survey coverage.

2 ‘Epidemic EIDs’ are those responsible for a Public Health Emergency of International Concern: Ebola, Zika, COVID and Mpox.

Many of the areas identified as being most reliant on US government funding for basic research – with the notable exception of HIV/AIDS – are areas with negligible or small levels of overall investment. If US government investment in these areas is not replaced by funding from other sources, then the lack of adequate funding for fundamental research poses a real risk for the future of scientific advancement and the potential to achieve a healthy R&D pipeline.

At the same time, the outsized role of NIH and its significant organisational focus on basic research – reflecting its institutional imperatives as a domestic science & technology agency and funder of fundamental research – means that funding for basic research in global health has remained fairly constant, despite significant changes in the state of science and product development over the last two decades. The share of NIH global health R&D funding devoted to basic research has remained stubbornly unchanged, for example, from 36.6% in 2008 to 36.5% in 2023, accounting for between 32% and 39% of NIH funding almost every year in between. In a world of plentiful funding for R&D, this may be an ideal allocation of resources, providing a steady level of support for fundamental research in order to hopefully generate transformative insights and provide a steady stream of new candidates for the R&D pipeline. But in a world of constrained investment, there is space for reflection about the optimal allocation of funding across the R&D continuum in different diseases, especially in a world of sharply declining ODA, and where the predominant class of investors in health research may be focused on domestic science & technology imperatives.

Which areas are best placed to deal with reduced US involvement?

So, how might the global health sector navigate the partial withdrawal of its biggest funder?

Rather than treating global health R&D as a single homogenous entity, it is worth exploring the potential resilience of different areas to a sharp reduction in US government funding. Unsurprisingly, one of the factors supporting resilience is the degree of reliance on the US government and the share of (sustainable) funding from other sources, including from the philanthropic and private sectors. Some good news here is that most private sector funding has risen steadily in recent years in some key areas. Excluding funding for COVID (which has unsurprisingly declined sharply since the pandemic) overall private R&D spending is up by $94m (12%) in real terms since 2020; this includes big increases in funding for some of the neglected tropical diseases, which have been particularly neglected by industry, along with rapid growth in already commercially significant areas like dengue and sexually transmitted infections, and in newer areas like chikungunya and leprosy.

The other group of products are those that manage a happy medium of relatively healthy private and philanthropic funding, along with substantial contributions from the US government. This list is headed by late-stage HPV vaccines (31% US, 21% private, 37% philanthropic), most early-stage R&D for diarrhoeal diseases and early-stage drugs targeting TB, HIV and helminths. These areas may have features – like the potential for spillover into high-income country markets – that make them inherently appealing to different kinds of funders. Or they may have benefited from savvy marketing, or sheer good luck. What is clear, though, is that these sorts of areas are much better positioned to weather shifts in US policy than areas which remain almost entirely reliant on the US government, and often the NIH alone.

What factors drive high levels of US dependence, and what can be done about it?

Beyond pointing to specific areas where US funding dominates, we can look for patterns in US funding share using regression analysis to determine how the US funding share tends to shift across different categories of funding.

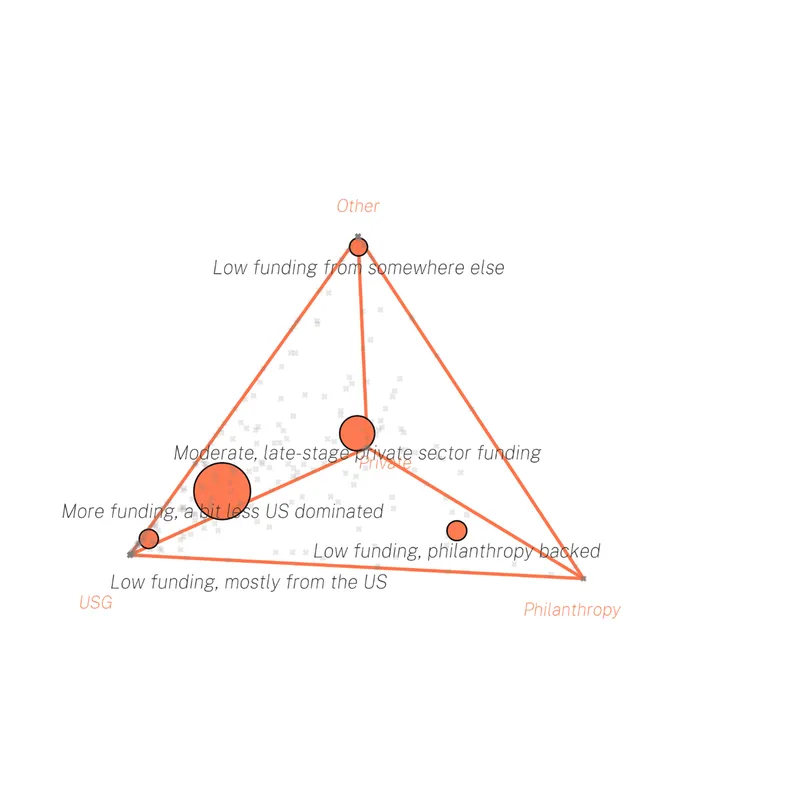

Our analysis shows that US global health R&D funding is not just large – it’s structurally skewed. Regression and cluster analysis of 300+ disease-product-stage areas reveal consistent patterns that can guide both mitigation and investment strategies.

US funding is concentrated at the start of the pipeline. Early-stage areas are far more dependent on the US than late-stage ones, with the shift from early to late-stage development predicting a 19-point drop in US share.

Relative to other funders, the US focus more on basic research and biologics than it does on vaccines, though in absolute terms, vaccine funding continues to swamp that of biologics. The tilt towards biologics may be a consequence of their current relatively high per-patient cost, which may make private and philanthropic funders sceptical of their potential in LMICs and push them towards funders, like the DOD, for whom the cost of a nationwide distribution is of secondary importance. The US government’s relatively lower share of the funding provided for late-stage vaccine trials likely reflects the very high cost of Phase III trials, which are far larger than drug or diagnostic trials, and the fact that outside strong commercial markets, these trials typically proceed only when they can receive support from multiple sources

Gynaecological and neglected EID areas are uniquely exposed to drops in US funding emerging from our analysis as the most dependent and least diversified areas.

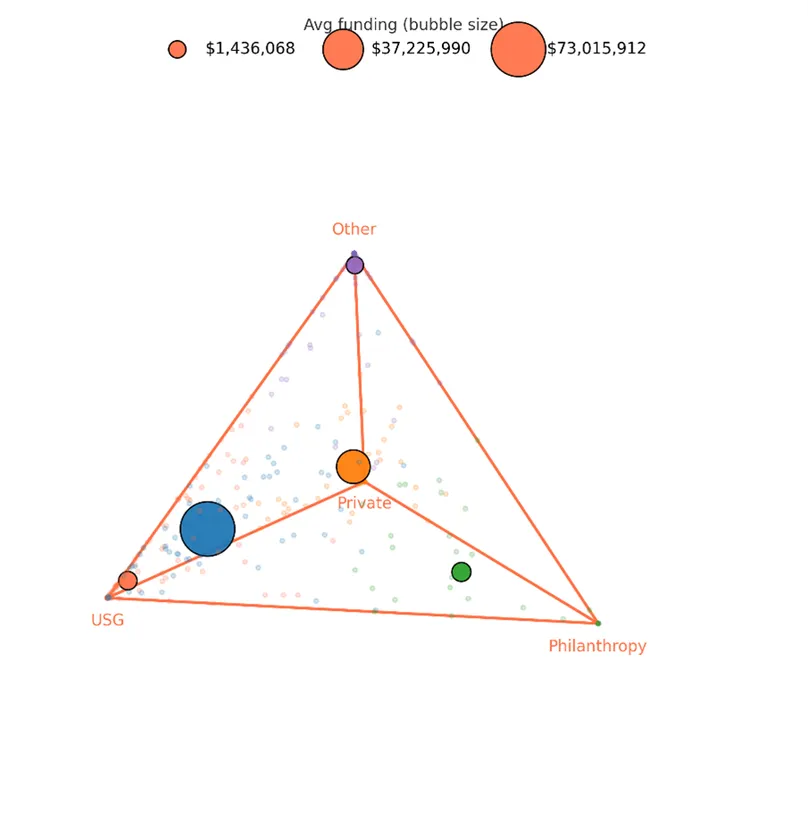

Finally, we can use cluster analysis to identify groups of areas which are statistically similar across the different categories we use to measure them: their disease and product area, but also their share of US, philanthropic and private sector funding, and the area of global health they relate to. This analysis identifies five distinct clusters across the 306 different combinations we have captured:

1. The first group (‘low funding, mostly from the US’) is the largest and includes around a third of our sample: 114 areas, mostly poorly funded (median $1.8m, none over $10m/year), US-dominated (averaging 84% US share against 2% private and 3% philanthropic), skewed to early-stage programs with a diagnostic and biologics focus, leaning towards EIDs without recent epidemics (‘nonepidemic EIDs’) and gynaecological R&D. These areas are very vulnerable to US funding cuts – insulated only by the fact that they already receive very little funding.

2. The second largest group (‘more funding, a little less US dominated’), with 67 areas, is mostly much better funded (median $35m/year), with a slightly lower level of US dominance (62%, against 9% private and 10% philanthropic), leaning towards early-stage and especially basic research, along with a substantial share of vaccines and an emphasis on the ‘big 3’ neglected diseases (TB, malaria and HIV) and the EIDs responsible for recent epidemics. While proportionately less exposed to US funding cuts, these areas tend to have much more to lose, with high absolute levels of funding and typically only a little philanthropic or private sector funding.

3. The third group (‘low funding, philanthropy-backed) is much more philanthropy-driven (68%), focused on late-stage biologics and VCPs, with relatively small budgets (median $1.2m/year, 86% under $10m/year), across a mix of multi-disease and ‘big 3’ ND areas. These areas are mostly outside the immediate blast radius of US cuts, since they combine less US-centric funding with having little left to lose.

4. The fourth group (‘moderate, late-stage private sector funding’) is private sector dominated (66% of funding), with moderate spending (median $9m). Activity is mostly late-stage and drug-titled, along with some vaccine development. The high private share reflects firms advancing their own candidates, typically on a for-profit basis. Their work concentrates on neglected diseases outside the ‘big 3’ and WHO-listed NTDs (including late-stage drug development for leprosy, kinetoplastids and helminths), sometimes with the help of public or philanthropic co-funding.

The fifth and final group (‘low funding from somewhere else’) is an odd mix of residual areas, heavily reliant on public funding from outside the US, especially the EU. They are mostly not dominated by any of the three sectors we consider (mean shares: US 8% / Private 1% / Philanthropy 5%), are skewed towards late-stage research, with a median funding of just $0.5 million per year and a focus on vaccines, diagnostics, and VCP. These areas mostly sit outside our analysis, with little funding from anywhere, and almost none from our key sectors.

Figure 6, below, illustrates how these clusters break down across the various funding shares by sector and across the different elements of global health R&D that we cover.

Figure 6. Distribution of R&D clusters by sector funding share

[1] See Figure 7 for an outline of US funding by global health area over time.

Where to now for global health?

How, and where, funders can help to fill the gap left by US cuts

The prospective loss of funding from the principal public backer of global health R&D cannot be minimised. If even a fraction of the attempted cuts analysed in this report eventuate, they will significantly reduce the amount of funding flowing to global health, likely for years to come.

Figure 7. Historical and projected US public funding by global health area

G-FINDER data with 2026 projection based on the Presidential Budget Request

Note that global health areas other than neglected disease were added to the G-FINDER survey gradually, starting (with Ebola) in 2014. Zero values reflect exclusion from the survey in that year.

We can take a little comfort from the knowledge that, though significant, the projected cuts will not take us to hitherto unseen lows in global health R&D funding. US public funding has grown materially over the last ten years, despite a decline from peak pandemic levels, and even the proposed cuts to future budgets would only partly undo that decade of growth. But the world, and the distribution of US funding, has changed since 2017. Assuming, as we do in Figure 7 above, that global health areas are impacted in proportion to the 2023 funding they received from each US government entity, the projected cuts in 2026 funding would leave US public funding for women’s health at its lowest level since 2018, and neglected disease R&D at by far its lowest level on record. While we continue to project relatively robust EID funding, other areas of global health R&D do face an unprecedented crisis.

In this light, while we in the global health community must maintain a sense of proportion as to the scale of the damage, it is important not to read the headline estimates in isolation. The R&D ecosystem and the pipeline have expanded in response to that decade of growth, and current commitments, platforms, and late-stage work now assume and rely on funding levels that are significantly higher than they were ten years ago. A reduction of this magnitude, therefore, risks destabilising programmes that did not exist a decade ago.

In response to the cuts in US funding, we suggest the following concrete steps:

First, identify and support promising projects that have been abandoned during the final stages of development. While no single organisation can replicate the role played by the NIH and BARDA, terminated grants – both now and in the future – likely include late-stage work which requires only a little additional support to push it over the line, and which will go to waste if their development is interrupted. The often-arbitrary process by which projects have been terminated, and the progress made before termination, means that stepping in to replace US funding may often have a higher projected return on investment than funding entirely new proposals.

Second, sustain shared R&D infrastructure in the hopes of a change in policy. After the surge of investment brought about by the COVID pandemic, we highlighted the difficulties faced by a historically lean R&D sector in absorbing a huge, sudden influx of funding. With the US in the process of unlearning the lessons COVID taught us about the importance of maintaining infrastructure and continuity of funding, other funders should do what they can to preserve the resources – particularly the human capital – built up during the years of relatively generous US spending. This means finding roles for the researchers and service providers who suddenly lost their means of support, and keeping the lights on – literally and figuratively – at the institutions built in response to COVID during the lean years to come.

Third, identify the areas hardest hit. This report begins the work of identifying the actual projects impacted by funding cuts: in general terms, basic research and early-stage vaccine R&D will bear a disproportionate impact from the current and proposed future cuts; more specifically, funding for maternal and gynaecological health are incredibly reliant on the US government; more specially still, 38 different areas of research report no non-US funding at all. Not all of this funding will be able to be replaced, but funders ought to be aware that literally no one else is supporting, say, late-stage drugs for polycystic ovary syndrome.

To make this analysis possible, there is more work to be done in charting the impact of funding cuts: while we can point to the areas impacted by specific grant terminations, much of the analysis we present assumes that organisations will cut funding in proportion to how they currently spend it – so that cuts to the NIH, for example, will mean a lot less basic research and only a little less biologics. These assumptions are the best we can do given the impossibility of modelling cuts that have not yet been enacted, but they are no substitute for continuing to monitor US government funding and determining where the actual impact has fallen.

Finally, the most difficult step will be to decide what needs saving and, by implication, what doesn’t get saved. Priority setting in global health is an incredibly difficult task, suddenly made more difficult by an influx of newly stranded opportunities and an outflux of funding. We have long argued that there should be more money for global health and fewer impossible choices for funders to make, but we now find ourselves in the opposite situation: one where every decision – and every dollar – matters more.