From TB prevention to cancer: the BCG vaccine treating bladder cancer

By Impact Global Health 19 January 2026

From TB prevention to cancer: the BCG vaccine treating bladder cancer

Every breakthrough in global health sends ripples that reach far beyond borders. In an era of fiscal tightening and inward-facing policy priorities, investments in global health R&D are under increasing pressure. Yet these investments are among the most powerful drivers of innovation, economic growth, and resilience – not just for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), but for high-income countries (HICs) as well. Impact Global Health demonstrated that $71 billion in global health R&D funding from 2007– 2023 catalysed $511 billion in GDP growth, 643,000 jobs, and 20,000 patents, a multiplier effect proving that global health investment drives domestic prosperity. The Ripple Effect 2.0 project further examines this dynamic through three case studies of innovations originally developed for LMIC needs that later delivered measurable health and economic benefits in HICs.

This case study focuses on the benefits of the BCG vaccine, originally developed from preventing tuberculosis (TB), which is now used as an alternative to chemotherapy in the treatment of bladder cancers in high income countries.

Innovation pathway

The Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) was developed over a hundred years ago from an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis (the bovine strain of the TB bacterium) by two French Scientists working at the Institut Pasteur. It remains the only registered TB vaccine, with reasonable efficacy against severe childhood TB but offering only weak protection for adults.

One of BCG’s mechanisms of action against TB – its stimulation of a Th-1 immune response – led to speculation that it could also generate an immune reaction against cancer cells, harnessing the body’s own immune system to attack a tumor. Bladder cancer was identified, in the 1970s, as a particularly good candidate for this treatment because early-stage bladder cancers (‘non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer’ or NMIBC) are contained in a hollow organ with tumors mostly located on its surface, allowing the treatment to ‘soak in’ to the affected area. Following a series of clinical trials in the 70s and 80s, BCG was gradually adopted as the standard of care for serious cases of NMIBC, partially displacing chemotherapy and surgical removal and delivering lower rates of recurrence and progression in more serious tumors.

The evolving use of BCG, from a tool against a neglected disease to a playing a key role in treating cancers in high-income countries, demonstrates the potential for biomedical R&D to deliver value in unexpected ways, sometimes decades after an initial discovery.

- A vaccine originally developed for tuberculosis, BCG, is now widely used in high-income countries as an effective treatment for bladder cancer, offering a key alternative to chemotherapy.

- By 2050, BCG’s role in cancer treatment is projected to prevent 877,000 returning cancers, save 296,000 lives, and avert 4.4 million DALYs in HICs.

- The value to society of the lives saved by BCG is nearly $1.5 trillion, alongside nearly $15 billion in health-system cost savings across all four markets.

Health impact in the USA, EU, UK and Japan

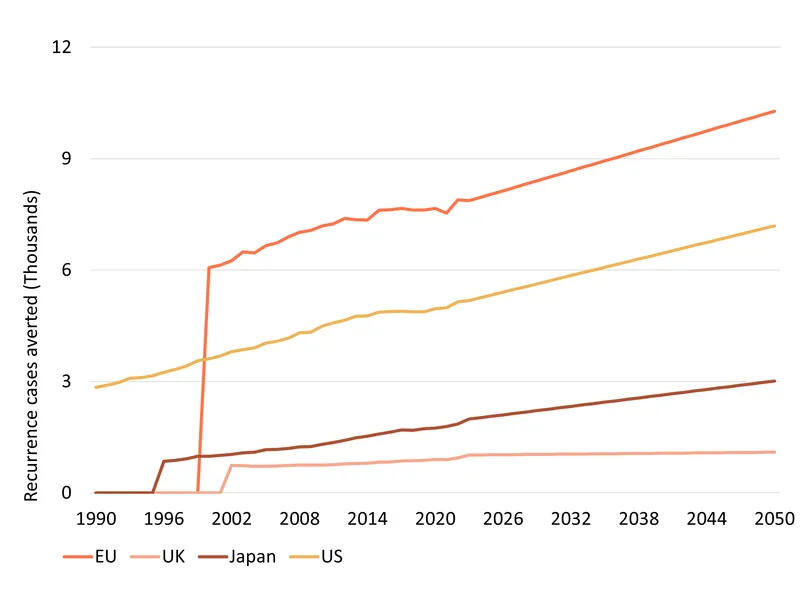

We estimate that, by 2050, BCG will prevent the recurrence – cases where a tumour reappears following an initially successful treatment – of nearly 877,000 bladder cancers and the progression of a little over 100,000. In turn, this will save about 296,000 lives, and avert nearly 4.4 million (discounted) DALYs across the EU, UK, the US and Japan. The geographic distribution of health impact mostly reflects differences in population size, though older populations like Japan’s experience more serious cases of bladder cancer, increasing the benefit they receive from BCG’s ability to reduce progression and recurrence. Varying dates of formal introduction of BCG, ranging from 1990 in the US to 2002 in the UK drive the time from which measured health gains occur, but likely understate off-label use of BCG prior to explicit regulatory approval.

As HIC populations continue to grow older over the next several decades, better ways of treating cancer will become increasingly valuable, driving gradual growth in the value delivered by BCG.

Economic impact

Being alive and in good health is something individuals and society consider extremely important. Health economists can place a dollar value on healthy life using the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL) approach, which approximates that value mostly based on how willing people are to take on risky jobs. On this basis, which sets the value of a US life at around $13 million, we estimated the societal gains from the projected 4.4 million DALYs averted to be worth more than US $1.5 trillion1 across our four markets.

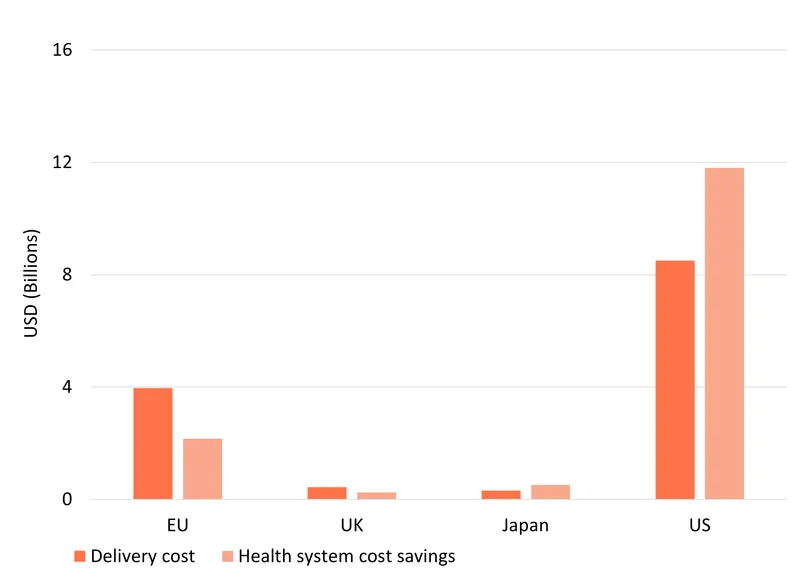

Using BCG in place of chemotherapy, while more expensive at first instance, also generates substantial net cost savings for health systems, by averting future recurrent cases and avoiding progression to far more costly muscle-invasive cancers. We estimate that the 109,619 instances of progression and 876,958 recurrences averted by BCG, would have generated a total of $14.7 billion in health care costs, most of which ($11.8 billion) would have occurred in the US – a large market with very high cancer treatment costs.

These savings need to be offset against the cost of delivering BCG, which is typically slightly more expensive on a per-dose basis than the chemotherapy it replaces, and which requires more doses and therefore also more labour to administer. We estimate these additional costs of choosing BCG rather than chemotherapy at $13.2 billion across our four markets, based on projected per-dose prices and administration costs. In the relatively most expensive health systems of the US and Japan, these additional costs are outweighed by the savings from avoiding recurrence and progression, meaning that BCG will save the US nearly $10 billion even taking into account its additional cost, and Japan around $200 million. In the UK and the EU, where future cases are able to be treated more cheaply, the health system costs of BCG outweigh its purely financial health system impact, with a net projected health system cost – extra BCG cost minus projected savings – of $1.8 billion in the EU and a little under $200 million in the UK.

These figures allow us to estimate the incremental cost effectiveness of BCG’s use against bladder cancer – the cost to the health system of each DALY it averts. In the US and Japan these values are negative, since BCG both saves money and improves health, making it clearly better than the chemotherapy alternatives. Even in the UK and EU, where BCG does impose net costs on the health system, its projected DALY gains are so large that the cost per DALY (incremental cost effectiveness ratio, or ICER) is trivially low: $875 per DALY in the EU and $917 in the UK – far below the kinds of maximum cost effectiveness thresholds used in high-income health systems, which are typically willing to spend tens of thousands of dollars per DALY.

Developing modern vaccines is an expensive process. Over the last two years alone, funders have devoted at least $150m to the late-stage trials of the M72 TB vaccine – a potential successor to BCG which will hopefully improve on its weak performance in adults. One hundred and fifty million dollars is both a lot of money in the context of global health R&D and completely trivial when compared to what HICs spend on health care. It represents only around 2% of the amount BCG will save high-income health systems by 2050 and just one ten-thousandth of the value of the lives BCG will save. While we have no way of knowing which of today’s candidates will become the next BCG, finding even one would pay for all of our global health R&D dozens of times over.

1 For ease of comparison, all monetary values are reported in inflation-adjusted 2025 US dollars

Conclusions

The evolving role played by BCG demonstrates the ability of global health R&D to deliver benefits in unexpected ways, in unexpected places. Funding for biomedical R&D is a global public good in the narrow sense that a new vaccine can be replicated and distributed anywhere in the world, but also in a broader sense: new discoveries can generate new opportunities for treatment and research far from where they began. Funding which was initially seen as an investment in faraway lives can also end up saving lives at home.

Key assumptions

Data on incidence of NMIBC is based on Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data for bladder cancer by age and country through to 2023, and projected into the future based on a linear extrapolation of past trends applied to future population by age – assuming a constant share of the high risk NMIBC for which BCG is indicated.

The chief simplifying assumptions made in the model are:

- Assuming full access to BCG for all patients for which it would be recommended – in reality shortages of BCG have restricted the number of doses used, though to an unknown extent. This overstates the past benefits (and also costs) of BCG to the extent is assumes more patients treated than was actually the case.

- Using UK definitions of approved population rather than separate clinical guidelines for each nation. This decision was taken in order to be able to model consistent patient populations on the basis of UK-specific efficacy data. This is likely to understate the amount of BCG used and therefore its impact (and cost) in other markets since, anecdotally, non-UK systems are likely to recommend BCG for cancers classed as ‘intermediate risk’. There is also some evidence that UK clinical practice is more liberal than NICE guidelines, further suggesting that our headline estimates understate the amount and impact of BCG.

- Treating mortality from recurrent cases equivalently to overall NMIBC case specific mortality. Recurrence-specific mortality data was not available, requiring us to model recurrence as a standard case. Given that recurrence in our model excludes cases of progression, which are modelled separately, it is not clear the direction of bias this assumption introduces.

- Treating all fatalities as being averted in the year of BCG treatment rather than over a multi-year period. This matters only from a discounting perspective – future benefits are treated a 2% less valuable for each intervening year – and introduces a small upward bias in estimated impact, since benefits are counted artificially quickly. Average times between treatment and counterfactual mortality are difficult to estimate and are likely less than 2 years on average.

- International costs of treatment are anchored to the UK values for which detailed data is available and then adjusted based on an overall index of health care costs in the UK and the target nation.

- The loss of quality of life (‘life years disabled’ or YLD in GBD terminology) from both progression and recurrence are assumed to persist for exactly one year prior to mortality or recovery. This likely overstates the duration of suffering in some cases, and significantly understates it in others. The net effect is, we believe, a slight upward bias on our estimates of health impact, though YLDs in any case account for only around 10% of total health gains.