Sexual & Reproductive Health

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

Overview

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex endocrine (hormonal) disorder affecting as many as 21% of women of childbearing age globally, although up to 70% of cases go undiagnosed. It is characterised by hormonal imbalance and ovarian dysfunction, which increases the risk of infertility, metabolic issues such as type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance, and mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. PCOS is also associated with pregnancy-related complications, including gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and preterm birth. Recent studies have also suggested a link with liver disease and an increased susceptibility to endometrial cancer due to sustained estrogen exposure.

Unmet needs

There is a need for both standardised protocols and improved diagnostics for PCOS, and better therapeutics to treat it. Current best diagnostic practices rely on clinical evaluation and the Rotterdam criteria, which require at least two of the following three features: irregular or absent ovulation, elevated androgen levels (hormones responsible for male sexual characteristics), and the presence of more than 12 ovarian follicles on ultrasound. However, diagnosis is often hindered by inconsistent application of protocols, a lack of standardised biochemical thresholds, and limited access to the tools needed to confirm diagnostic criteria. There is no cure for PCOS, with current treatments – oral contraceptives, metformin, hormone-regulating medications, and fertility medications – offering only limited symptomatic management. Access to treatment in LMICs is further restricted by cost, availability, and infrastructure challenges. Novel therapies are needed, with SGLT2 inhibitors (blood sugar inhibitors), GLP-1 agonists (appetite regulators), and targeted biologics (e.g. stem cells and exosomes) in development to improve long-term management and address PCOS’s underlying pathophysiology.

Funding

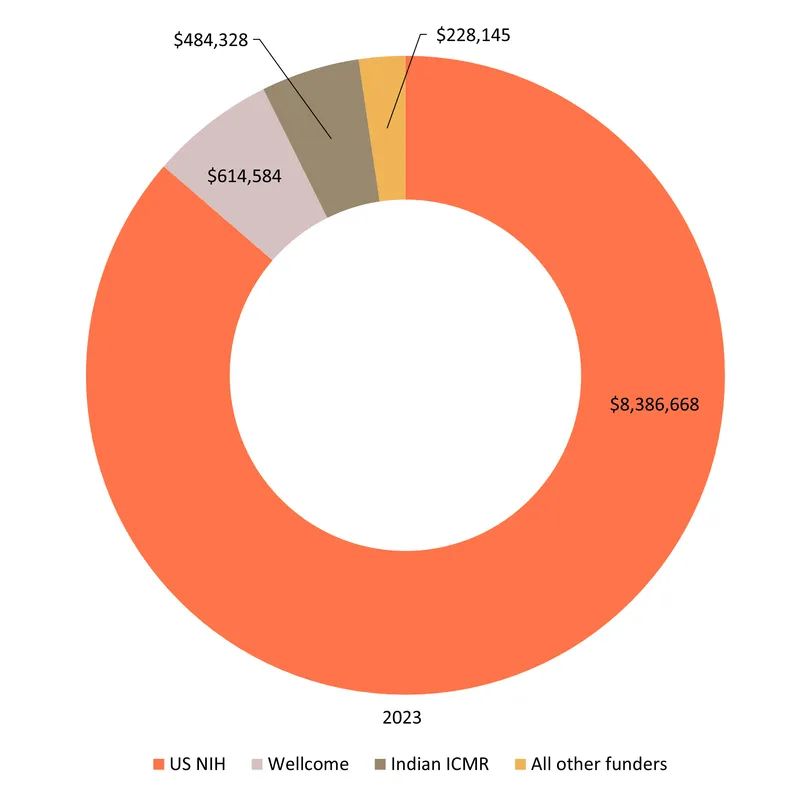

Funding for PCOS totalled $9.7m in 2023. As with many other gynaecological conditions, a clear majority of all PCOS funding in 2023 was for basic research ($7.2m, 74%). The second largest share went to diagnostics ($1.3m, 14%), followed by drugs ($0.8m, 8%). No funding was reported for PCOS biologics.

Only 6% ($0.5m) of funding was for clinical development, all of it for an NIH-funded Phase III trial of semaglutide – the well-known diabetes and weight loss drug, which shows promise in treating the weight gain and metabolic syndrome caused by PCOS. The NIH provided 86% of funding overall, and almost all of the funding for product development, with the only exceptions being $0.2m for a preclinical study on 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitors from the Indian ICMR and $9k for early-stage diagnostics from the Indian BIRAC.

There was no funding from industry or multilaterals reported through the G-FINDER survey.

Alongside the NIH, three Indian public funders – ICMR, BIRAC and the DBT – provided just over 6% of total funding ($0.6m) between them, leaving PCOS with the largest LMIC funding share of any individual SRH condition.

The relatively large share of funding provided by Indian governmental organisations ($0.6m, 6% of total funding) could reflect their higher rates of participation in the survey, but also India’s relatively high prevalence of PCOS.

Wellcome accounted for most of the remaining funding and provided a further $0.6m (6.3% of the total) for basic research on androgen excess and metabolism.

Funding for PCOS

Product landscape & pipeline

Despite the high prevalence of PCOS, research for new treatments and diagnostics is limited. As with other women’s health conditions, the cause of PCOS is not well understood, with current research pointing towards a group of disorders with overlapping metabolic and reproductive manifestations, with several subtypes arising from distinct causal pathways. This complexity lends itself to a more diverse and extensive biomedical landscape, with PCOS hosting a greater number of products in use or in development than other gynaecological conditions. This reflects a fragmented symptomatic approach to a multi-faceted but poorly understood pathology rather than sustained R&D efforts.

Because of the diverse clinical manifestations of PCOS, the landscape is characterised by the largest number of repurposed drugs used or investigated off-label, for example, to address metabolic disturbances or fertility issues, across gynaecological conditions in our scope. The absence of definitive treatment is only partially compensated by this symptomatic approach, as response to repurposed medicines presents important interindividual variations. The diagnostics pipeline is also rather active, with a strong focus on biomarker research, which both echoes the complexity of the disease while also offers interesting, targeted pathways for precision diagnostics. Most, however, are still in early development.

A total of 131 medicines are in use or in development for PCOS, including 45 marketed products and 86 candidates in development.

Forty-five marketed medicines for PCOS might appear like a high number of therapeutic options, but they are all repurposed, targeting specific symptoms of the condition only, with none addressing the underlying cause. These include anti-acneic (12) and anti-androgens (4) drugs to address symptoms of hyperandrogenism (overproduction of male hormones). Hormonal contraceptives are also widely used for the management of hyperandrogenism symptoms and menstrual regulation (10), but their use is associated with negative metabolic side-effects, such as insulin resistance, and of course is not indicated for women wishing to conceive. Marketed medicines also include fertility treatments, with 14 drugs and biologics routinely used for fertility treatments indicated for PCOS patients trying to conceive. Additionally, some drugs have been repurposed to address metabolic disturbances associated with the syndrome, such as the insulin sensitiser metformin, widely used for the treatment of PCOS since the 1990s, and anti-obesity medications like liraglutide, orlistat and semaglutide. While these medicines address different clinical manifestations of PCOS, they are used and investigated in combination with potential synergistic effects. Metformin is, for example, combined with fertility treatments for enhanced efficacy in PCOS populations, or with combined contraceptives to treat metabolic and hormonal issues with better results than each treatment alone.

Looking to the future, there are also 86 investigational medicines in the pipeline, including 81 drugs and five biologics, again, though the majority are repurposed medicines (62%, 53/86), with the same focus on metabolic and hormonal drugs for symptomatic relief rather than novel pathways or cures. Medicines impacting metabolic function constitute the largest category of PCOS investigational medicines (37%, 32/86). A quarter of all medicines in development for PCOS are marketed antidiabetics (21), generally investigated for their impact on metabolic and reproductive functions, often in comparison or combination with metformin. Others include obesity medications, statins (2) and saroglitazar, approved in India for treating hyperlipidemia in diabetes patients. Several new chemical entities in development for metabolic diseases (obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome) are also being investigated for PCOS, the most advanced being licogliflozin and dichloroacetate, both in Phase II.

Drugs under investigation also include those routinely used in other gynaecology conditions for menopause, cancer and fertility care (10 drugs), including GnRH antagonists and agonists, studied for their impact on hormonal and metabolic regulation, and fertility treatments. While the fertility indication is prominent with these gynaecological medications, alternative approaches are also explored to improve fertility outcomes, such as aspirin (Phase III), the osteoporosis drug alendronate (discovery) or the neurologic medication cabergoline to prevent ovarian hyper syndrome (Phase III).

Recent research has highlighted the association between PCOS and low-grade chronic inflammation, which is reflected in the investigation of eleven drugs for their anti-inflammatory properties. These include four repurposed drugs (glucocorticoids, NSAIDS, phlebotonics antioxidants) and seven NCEs developed for their anti-inflammatory role, also in the discovery and preclinical phase for PCOS.

A number of drugs marketed for a diversity of indications are also being tested for their potential benefits, such as antimalarial drugs, antihypertensives, antibiotics, anticoagulants and opioid antagonists, perhaps reflecting the limited understanding of the disease pathology and a willingness to explore any option with potential symptomatic benefit.

Biologics are also investigated for the treatment of PCOS, and include the standard fertility treatment corifollitropin alfa, two monoclonal antibodies in preclinical phases, faecal microbiota transplant (mice model) to address the metabolic and reproductive symptoms of PCOS and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (UCD-MSCs) therapy, undergoing Phase I/II investigations, after previous studies have shown promising results.

There also two devices in the pipeline: the contraceptive etonogestrel/ethinylestradiol vaginal ring investigated for both hormonal and metabolic regulation purposes, and continuous positive airway pressure therapy studied for its potential metabolic (insulin resistance) and reproductive benefits in PCOS patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Neither appears to be a definitive approach to support people with PCOS to manage their condition in the long term.

To diagnose PCOS, there are already 12 marketed diagnostics used as part of the Rotterdam criteria – a set of clinical criteria assessed in conjunction: ovarian morphology is measured via ultrasound, specifically ovarian volume and follicle count; hyperandrogenism is measured via several (9) hormone biomarker tests and other morphological assessments (such as the Modified Ferriman–Gallwey Score for hirsutism). While the Rotterdam criteria are widely used for PCOS diagnosis, their development was based on expert meetings rather than evidence-based treatment guidance, and they ignore clinical manifestations that might be essential to consider to distinguish phenotypes, such as metabolic parameters. There is a need for precision diagnostics that reflect all relevant symptoms, are more effective at predicting prognosis, including for fertility and cardiovascular risks, and potentially indicate physiological pathways relevant to the syndrome.

There are also 60 diagnostics in development, with some additional ultrasound measurements (8) and a suite of investigated biomarker tests (51).

Ultrasound-based candidates include a range of measurements of ovarian and uterine artery blood flow as well as two ultrasound assessments of tissue: measuring ovarian stiffness/elasticity or assessing ovarian stroma, which is influenced by the amount of collagen, blood flow, and other tissue characteristics and can appear hyperechoic (brighter) in PCOS due to increased tissue density and fibrosis.

Biomarker testing constitutes the bulk of diagnostic research for PCOS, although 96% of them are still in early development, meaning most are a long way off being a reality for the diagnosis of PCOS in a clinical setting (or otherwise). The 34 individual biomarkers investigated for their diagnostic potential for PCOS include alternative biomarkers to assess hyperandrogenism (dihydrotestosterone, SHGB pulsatility, serum mannose), and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), due to its correlation with ovarian follicle activity. A specific anti-Müllerian hormone biosensor is being developed by Indian researchers as a potential diagnostic tool for PCOS (early development). There are also 17 multi-biomarker tests in early development, including three conceptualised to be used at the point-of-care or at home: an at-home urinary androgen index, a portable aptamer device allowing for luteinising hormone assessment and the Woost menstrual blood at-home test kit.

The variety of biomarkers investigated (hormones, proteins, amino acids, lipid profile, immune-related biomarkers, and even fructose, mannose and vitamin D) highlights both the complexity and the limited understanding of the condition. But while still at the early stage, this field has the potential to offer both precision diagnostics and uncover specific pathological pathways to improve the overall understanding of the condition.

PCOS pipeline

The complexity of PCOS presents a unique opportunity for funders to drive transformative change in women's health. By investing in comprehensive research that unravels the pathophysiology of PCOS, we can pave the way for the development of targeted therapies and innovative diagnostic tools. Such advancements would not only improve the quality of life for those affected but also reduce the long-term healthcare costs associated with untreated or poorly managed PCOS. Furthermore, supporting research in this area aligns with broader goals of health equity, as PCOS disproportionately affects underserved populations who are mainly in LMICs and who often face barriers to diagnosis and treatment.